2-day workshop of “Design Thinking for Your Creative Practice 2025” was held on December 6 and December 7, 2025. This workshop can be applied as a part of the requirements for passing one of the ToTAL/Entrepreneurship Courses below:

-ENT.L202 Bachelor’s Fundamental Group Work for Leadership B

-ENT.V204 Bachelor’s Fundamental Group Work for Value Creation D

-TAL.A501/TAL.A601 Master’s/Doctoral Essential Group Work for Leadership F

-TAL.S506/TAL.S510 Recognition of Social Issues Workshop B/D

-TAL.W502/TAL.W503 Fundamental Group Work for Leadership I/II

| Facilitators | Thomas Both and David Janka (d.school, Stanford Univ.), Scott Witthoft (previously The University of Texas) |

| Date and Time | Day 1: Saturday, December 6, 2025, 9:00 a.m. – 6:00 p.m. Day 2: Sunday, December 7, 2025, 9:00 a.m. – 6:00 p.m. |

| Venue | S4-202 & S4-203, South Building 4, Ookayama Campus |

Day 1 — Cultivating the Beginner’s Mindset

The workshop opened with an intriguing question: If you were a scientist or a musician, when might you recognize yourself as already “working like a designer”. With this prompt, the facilitators encouraged us to think about design not as a specialized technical field, but as a mindset that draws from diverse domains. Among all the ideas we discussed, the one that left the strongest impression on me was the concept of maintaining a beginner’s mindset.

A beginner’s mindset, as the facilitators explained, is the ability to approach the world as though encountering it for the first time—free from preconceived notions or rigid expectations. They quoted Zen master Shunryu Suzuki: “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities; in the expert’s, there are few.” This quote perfectly encapsulated the core message: the more we think we “already know,” the less we actually see. Acting as beginners allows us to notice fresh insights that experts often overlook.

Before the workshop, we had been instructed to bring a banana. None of us understood why at the time. Only later did we discover that this was part of our first creative challenge: to “promote” the banana using classroom materials, drawing inspiration from a personal hobby or interest. The idea was to view an ordinary object—something so familiar that we rarely think about its characteristics—in a completely new and creative way.For my own theme, I chose stand-up comedy, something I personally enjoy. As I looked around the classroom for inspiration, I noticed a microphone at the front. To my surprise, the microphone and the banana were almost exactly the same length. This small observation led me to create the slogan: “Same length—one tastes good, both bring you happiness.” It was a simple idea, but it emerged from looking at my environment with fresh eyes. Without consciously adopting a beginner’s mindset, I would never have noticed such a small detail. My classmates also came up with creative ideas, like drawing Gemini and joking that “AI can do anything except eat bananas.” These exercises reminded all of us that creativity comes from curiosity and playful exploration, not from trying to be “right.”

In the afternoon, we left the classroom for fieldwork. We were instructed to visit a train station, observe the environment, and take notes using specialized sheets. The sheets had two parts: AEIOU (Actions, Environments, Interactions, Objects, Users) and “Why–How–What”. These tools forced us to observe intentionally rather than casually. Normally, when we walk through a station, especially one we use daily, we only look for what is relevant to us—our train, our transfer, our exit. But design thinking required us to slow down and watch everything: how people behave, what objects they use, how the environment guides (or fails to guide) movement, and what cultural messages the space communicates.

Our group visited Musashi-Kosugi Station, one of the busiest stations on the Tokyu Line and practically the heart of Kawasaki. There, we noticed something we had always ignored before: the station was filled with advertisements for local sports teams such as Kawasaki Frontale and the Brave Thunders. These posters weren’t just advertisements—they were expressions of local identity and community pride. It became clear that each station can reflect a unique “micro-culture,” something easy to overlook when simply rushing through. Other groups also shared interesting findings. One story stood out: a child had quietly watched a group conduct their observations for nearly 30 minutes. The idea of “observing the observers” was amusing, but it also reminded me once again of the true beginner’s mindset. Children constantly watch, question, and wonder. Their natural curiosity is precisely what allows them to learn so quickly. As future designers—or anyone hoping to innovate—we need to reclaim that curiosity rather than lose it as we grow older.

Day 2 — From Ideas to Prototyping

The second day focused on two crucial parts of design thinking: being generative (creating many possibilities) and being selective (choosing what to develop). We began with a discussion about Japan’s aging population problem. The task was to brainstorm freely, writing down as many ideas as possible without worrying about correctness or practicality. This exercise emphasized that generating ideas should be free of judgment—because evaluating ideas too early kills creativity.

We next shifted our focus to prototyping. One example shown to us was the Baugespanne, a Swiss installation used to visualize construction projects so local residents can understand a building’s future impact. This concept helped me realize that prototyping is not merely creating a model—it is about transforming abstract ideas into tangible experiences so that people can react to them.

Our prototyping activity involved imagining a family’s refrigerator with specific constraints: the family lived in an area prone to wildfires and had children with special dietary needs. My partner and I designed a three-section container with a movable partition. Amusingly, we realized afterward that we had designed it without fully understanding our own reasoning. As the facilitators said, big ideas happen first, but big questions drive the design.

When another group came to “interview” us, the emphasis was placed on listening to their questions and reactions, rather than on presenting how the concept was supposed to work. Their questions helped us understand our own design better. For example, when they asked why the partition was movable, we suddenly realized its benefit: adjustable space is crucial during emergencies for sorting supplies efficiently. Another question completely transformed our idea: “How does your product help the family if they need to evacuate immediately?”

We had not considered evacuation at all, but this question pushed us to redesign the container as a portable backpack, equipped with buckles and removable sections so the family could carry essential supplies during a wildfire. This moment demonstrated how engaging with others’ questions can reveal overlooked assumptions and meaningfully elevate a design.

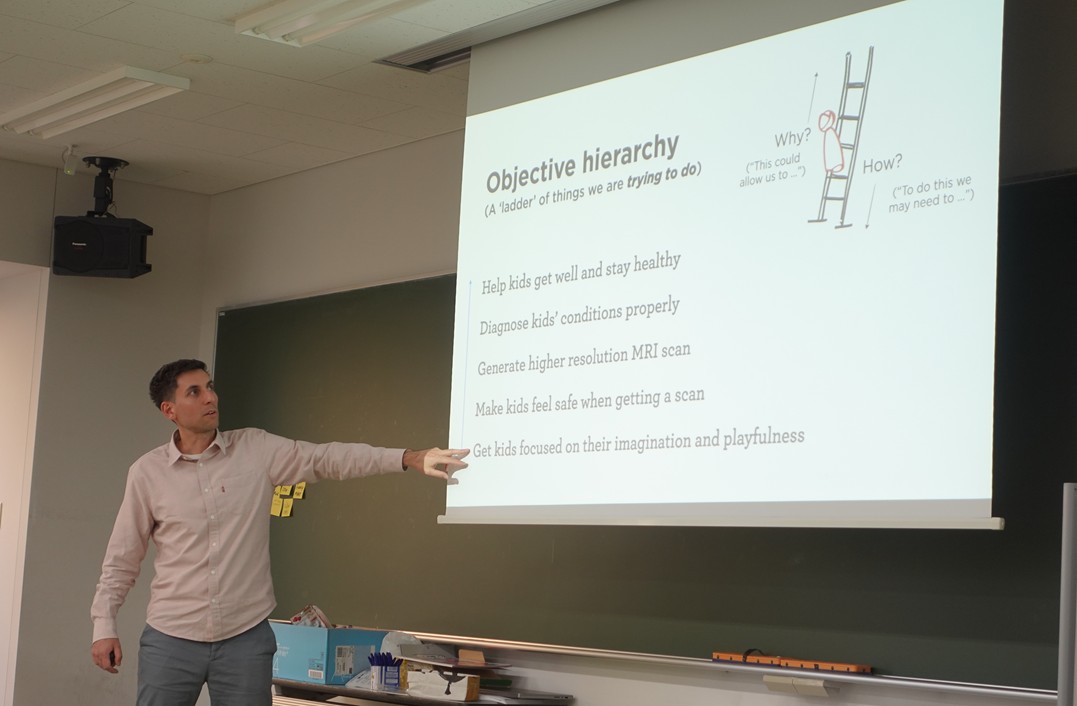

Following this prototyping activity, we watched a short promotional video produced by the Kobe Shimbun. It introduced a simple, two-page disaster-preparedness checklist. From this example, we were taught the Why–How Laddering technique: starting with a topic, moving upward to explore deeper motivations, and moving downward to identify actionable solutions. Initially, our group struggled to define our main topic clearly, but thanks to Mr.Both’s explanations and Mr.Janka’s team coaching, we soon understood the structure and created a clear ladder.

Finally, we completed a Why–How ladder for our project. Although I do research in economic experiments, I had never visualized my research questions like this. To my surprise, the diagram revealed insights I had never consciously noticed before. It also made me realize how useful such visualization tools are for explaining research to non-experts—something crucial in both academic and real-world communication.

Reflections

In summary, this workshop provided me with a fresh and empowering way to engage with the world. It taught me that design thinking is not just a method but a mindset—one that values curiosity, observation, and reflection. From bananas and microphones to train stations and emergency backpacks, every moment encouraged us to reconnect with our natural creativity.I believe everyone who participated felt the same sense of discovery. Whether in daily life or professional work, design thinking offers tools to think more clearly, listen more deeply, and create more meaningfully. It trains us to focus on the logical flow of ideas rather than being distracted by assumptions or superficial impressions. Most importantly, it reminds us to never lose our beginner’s mindset—a mindset full of possibilities.

Written by:

Haoyang Zou, B1, School of Engineering